Edward Sapir on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

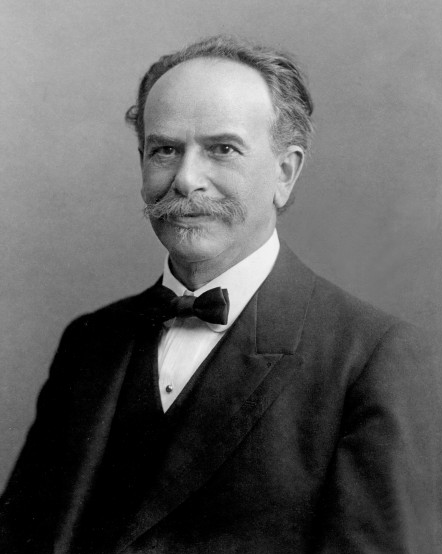

Edward Sapir (; January 26, 1884 – February 4, 1939) was an American Jewish anthropologist-

''

Sapir emphasized language study in his college years at Columbia, studying Latin, Greek, and French for eight semesters. From his sophomore year he additionally began to focus on Germanic languages, completing coursework in

Sapir emphasized language study in his college years at Columbia, studying Latin, Greek, and French for eight semesters. From his sophomore year he additionally began to focus on Germanic languages, completing coursework in

Although still in college, Sapir was allowed to participate in the Boas graduate seminar on American Languages, which included translations of Native American and Inuit myths collected by Boas. In this way Sapir was introduced to Indigenous American languages while he kept working on his M.A. in Germanic linguistics.

Although still in college, Sapir was allowed to participate in the Boas graduate seminar on American Languages, which included translations of Native American and Inuit myths collected by Boas. In this way Sapir was introduced to Indigenous American languages while he kept working on his M.A. in Germanic linguistics.

Sapir's first fieldwork was on the Wishram Chinook language in the summer of 1905, funded by the Bureau of American Ethnology. This first experience with Native American languages in the field was closely overseen by Boas, who was particularly interested in having Sapir gather ethnological information for the Bureau. Sapir gathered a volume of Wishram texts, published 1909, and he managed to achieve a much more sophisticated understanding of the Chinook sound system than Boas. In the summer of 1906 he worked on

Sapir's first fieldwork was on the Wishram Chinook language in the summer of 1905, funded by the Bureau of American Ethnology. This first experience with Native American languages in the field was closely overseen by Boas, who was particularly interested in having Sapir gather ethnological information for the Bureau. Sapir gathered a volume of Wishram texts, published 1909, and he managed to achieve a much more sophisticated understanding of the Chinook sound system than Boas. In the summer of 1906 he worked on

In 1915 Sapir returned to California, where his expertise on the Yana language made him urgently needed. Kroeber had come into contact with Ishi, the last native speaker of the Yahi language, closely related to Yana, and needed someone to document the language urgently. Ishi, who had grown up without contact to whites, was monolingual in Yahi and was the last surviving member of his people. He had been adopted by the Kroebers, but had fallen ill with

In 1915 Sapir returned to California, where his expertise on the Yana language made him urgently needed. Kroeber had come into contact with Ishi, the last native speaker of the Yahi language, closely related to Yana, and needed someone to document the language urgently. Ishi, who had grown up without contact to whites, was monolingual in Yahi and was the last surviving member of his people. He had been adopted by the Kroebers, but had fallen ill with

The

The

National Academy of Sciences biography

at spartan.ac.brocku.ca

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sapir, Edward 1884 births 1939 deaths People from Lębork Lithuanian Jews People from the Province of Pomerania American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent German emigrants to the United States Jewish American social scientists Linguists from the United States Linguists of Yiddish Anthropological linguists Interlingua Columbia College (New York) alumni University of Chicago faculty Yale University faculty Columbia University faculty Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Yale Sterling Professors Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Linguists of Na-Dene languages Linguists of Navajo Linguists of Algic languages Linguists of Siouan languages Linguists of Salishan languages Linguists of Hokan languages Linguists of Uto-Aztecan languages Linguists of Chinookan languages Linguists of Wakashan languages Linguists of Penutian languages Paleolinguists DeWitt Clinton High School alumni Linguistic Society of America presidents Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People from the Lower East Side 20th-century linguists Jewish anthropologists Linguists of indigenous languages of the Americas 20th-century American anthropologists Presidents of the American Folklore Society

linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

, who is widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics in the United States.

Sapir was born in German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, in what is now northern Poland. His family emigrated to the United States of America when he was a child. He studied Germanic linguistics at Columbia, where he came under the influence of Franz Boas, who inspired him to work on Native American languages

Over a thousand indigenous languages are spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. These languages cannot all be demonstrated to be related to each other and are classified into a hundred or so language families (including a large numbe ...

. While finishing his Ph.D. he went to California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

to work with Alfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber (June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the first ...

documenting the indigenous languages there. He was employed by the Geological Survey of Canada

The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC; french: Commission géologique du Canada (CGC)) is a Canadian federal government agency responsible for performing geological surveys of the country, developing Canada's natural resources and protecting the e ...

for fifteen years, where he came into his own as one of the most significant linguists in North America, the other being Leonard Bloomfield

Leonard Bloomfield (April 1, 1887 – April 18, 1949) was an American linguist who led the development of structural linguistics in the United States during the 1930s and the 1940s. He is considered to be the father of American distributionalis ...

. He was offered a professorship at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, and stayed for several years continuing to work for the professionalization of the discipline of linguistics. By the end of his life he was professor of anthropology at Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, where he never really fit in. Among his many students were the linguists Mary Haas

Mary Rosamond Haas (January 23, 1910 – May 17, 1996) was an American linguist who specialized in North American Indian languages, Thai, and historical linguistics. She served as president of the Linguistic Society of America. She was elected ...

and Morris Swadesh, and anthropologists such as Fred Eggan and Hortense Powdermaker

Hortense Powdermaker (December 24, 1900 – June 16, 1970) was an American anthropologist best known for her ethnographic studies of African Americans in rural America and of Hollywood.

Early life and education

Born to a Jewish family, Powdermak ...

.

With his linguistic background, Sapir became the one student of Boas to develop most completely the relationship between linguistics and anthropology. Sapir studied the ways in which language and culture influence each other, and he was interested in the relation between linguistic differences, and differences in cultural world views. This part of his thinking was developed by his student Benjamin Lee Whorf

Benjamin Lee Whorf (; April 24, 1897 – July 26, 1941) was an American linguist and fire prevention engineer. He is known for " Sapir–Whorf hypothesis," the idea that differences between the structures of different languages shape how the ...

into the principle of linguistic relativity or the "Sapir–Whorf" hypothesis. In anthropology Sapir is known as an early proponent of the importance of psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between ...

to anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

, maintaining that studying the nature of relationships between different individual personalities is important for the ways in which culture and society develop.

Among his major contributions to linguistics is his classification of Indigenous languages of the Americas, upon which he elaborated for most of his professional life. He played an important role in developing the modern concept of the phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

, greatly advancing the understanding of phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

.

Before Sapir it was generally considered impossible to apply the methods of historical linguistics

Historical linguistics, also termed diachronic linguistics, is the scientific study of language change over time. Principal concerns of historical linguistics include:

# to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages

# ...

to languages of indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

because they were believed to be more primitive than the Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

. Sapir was the first to prove that the methods of comparative linguistics were equally valid when applied to indigenous languages. In the 1929 edition of ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' he published what was then the most authoritative classification of Native American languages, and the first based on evidence from modern comparative linguistics. He was the first to produce evidence for the classification of the Algic

The Algic languages (also Algonquian–Wiyot–Yurok or Algonquian–Ritwan) are an indigenous language family of North America. Most Algic languages belong to the Algonquian subfamily, dispersed over a broad area from the Rocky Mountains to ...

, Uto-Aztecan, and Na-Dene languages

Na-Dene (; also Nadene, Na-Dené, Athabaskan–Eyak–Tlingit, Tlina–Dene) is a family of Native American languages that includes at least the Athabaskan languages, Eyak, and Tlingit languages. Haida was formerly included, but is now consider ...

. He proposed some language families

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ''ancestral language'' or ''parental language'', called the proto-language of that family. The term "family" reflects the tree model of language origination in hi ...

that are not considered to have been adequately demonstrated, but which continue to generate investigation such as Hokan

The Hokan language family is a hypothetical grouping of a dozen small language families that were spoken mainly in California, Arizona and Baja California.

Etymology

The name ''Hokan'' is loosely based on the word for "two" in the various Hokan ...

and Penutian

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language families that includes many Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. The existence of a Penutian s ...

.

He specialized in the study of Athabascan languages

Athabaskan (also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large family of indigenous languages of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, Pacific C ...

, Chinookan languages

The Chinookan languages were a small family of languages spoken in Oregon and Washington along the Columbia River by Chinook peoples. Although the last known native speaker of any Chinookan language died in 2012, the 2009-2013 American Community ...

, and Uto-Aztecan languages, producing important grammatical descriptions of Takelma

The Takelma (also Dagelma) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Rogue Valley of interior southwestern Oregon.

Most of their villages were sited along the Rogue River. The name ''Takelma'' means "(Those) Along the River".

His ...

, Wishram, Southern Paiute. Later in his career he also worked with Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, and Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

, as well as Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, E ...

, and he also was invested in the development of an International Auxiliary Language.

Life

Childhood and youth

Sapir was born into a family ofLithuanian Jews

Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks () are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern Suwałki and Białystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent are ...

in Lauenburg

Lauenburg (), or Lauenburg an der Elbe ( en, Lauenberg on the Elbe), is a town in the state of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is situated on the northern bank of the river Elbe, east of Hamburg. It is the southernmost town of Schleswig-Holstein ...

(now Lębork) in the Province of Pomerania where his father, Jacob David Sapir, worked as a cantor

A cantor or chanter is a person who leads people in singing or sometimes in prayer. In formal Jewish worship, a cantor is a person who sings solo verses or passages to which the choir or congregation responds.

In Judaism, a cantor sings and lead ...

. The family was not Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

, and his father maintained his ties to Judaism through its music. The Sapir family did not stay long in Pomerania and never accepted German as a nationality. Edward Sapir's first language was Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

, and later English. In 1888, when he was four years old, the family moved to Liverpool, England, and in 1890 to the United States, to Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. Here Edward Sapir lost his younger brother Max to typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

. His father had difficulty keeping a job in a synagogue and finally settled in New York on the Lower East Side, where the family lived in poverty. As Jacob Sapir could not provide for his family, Sapir's mother, Eva Seagal Sapir, opened a shop to supply the basic necessities. They formally divorced in 1910. After settling in New York, Edward Sapir was raised mostly by his mother, who stressed the importance of education for upward social mobility, and turned the family increasingly away from Judaism. Even though Eva Sapir was an important influence, Sapir received his lust for knowledge and interest in scholarship, aesthetics, and music from his father. At age 14 Sapir won a Pulitzer scholarship to the prestigious Horace Mann high school, but he chose not to attend the school which he found too posh, going instead to DeWitt Clinton High School

, motto_translation = Without Work Nothing Is Accomplished

, image = DeWitt Clinton High School front entrance IMG 7441 HLG.jpg

, seal_image = File:Clinton News.JPG

, seal_size = 124px

, ...

,Allyn, Bobby"DeWitt Clinton's Remarkable Alumni"''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', July 21, 2009. Accessed September 2, 2014. and saving the scholarship money for his college education. Through the scholarship Sapir supplemented his mother's meager earnings.Darnell 1990:1–4

Education at Columbia

Sapir entered Columbia in 1901, still paying with the Pulitzer scholarship. Columbia at this time was one of the few elite private universities that did not limit admission of Jewish applicants with implicit quotas around 12%. Approximately 40% of incoming students at Columbia were Jewish. Sapir earned both aB.A.

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

(1904) and an M.A.

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

(1905) in Germanic philology

Germanic philology is the philological study of the Germanic languages, particularly from a comparative or historical perspective.

The beginnings of research into the Germanic languages began in the 16th century, with the discovery of literary tex ...

from Columbia, before embarking on his Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

in Anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

which he completed in 1909.

College

Sapir emphasized language study in his college years at Columbia, studying Latin, Greek, and French for eight semesters. From his sophomore year he additionally began to focus on Germanic languages, completing coursework in

Sapir emphasized language study in his college years at Columbia, studying Latin, Greek, and French for eight semesters. From his sophomore year he additionally began to focus on Germanic languages, completing coursework in Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

, Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old High ...

, Old Saxon

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German (spoken nowadays in Northern Germany, the northeastern Netherlands, southern Denmark, the Americas and parts of Eastern Europe). It ...

, Icelandic, Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

, and Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

. Through Germanics professor William Carpenter, Sapir was exposed to methods of comparative linguistics that were being developed into a more scientific framework than the traditional philological approach. He also took courses in Sanskrit, and complemented his language studies by studying music in the department of the famous composer Edward MacDowell

Edward Alexander MacDowell (December 18, 1860January 23, 1908) was an American composer and pianist of the late Romantic period. He was best known for his second piano concerto and his piano suites '' Woodland Sketches'', ''Sea Pieces'' and '' ...

(though it is uncertain whether Sapir ever studied with MacDowell himself). In his last year in college Sapir enrolled in the course "Introduction to Anthropology", with Professor Livingston Farrand

Livingston Farrand (June 14, 1867 – November 8, 1939) was an American physician, anthropologist, psychologist, public health advocate and academic administrator.

Early life and education

Born in Newark, New Jersey, to Dr. Samuel Ashbel Far ...

, who taught the Boas "four field" approach to anthropology. He also enrolled in an advanced anthropology seminar taught by Franz Boas, a course that would completely change the direction of his career.

Influence of Boas

Although still in college, Sapir was allowed to participate in the Boas graduate seminar on American Languages, which included translations of Native American and Inuit myths collected by Boas. In this way Sapir was introduced to Indigenous American languages while he kept working on his M.A. in Germanic linguistics.

Although still in college, Sapir was allowed to participate in the Boas graduate seminar on American Languages, which included translations of Native American and Inuit myths collected by Boas. In this way Sapir was introduced to Indigenous American languages while he kept working on his M.A. in Germanic linguistics. Robert Lowie

Robert Harry Lowie (born '; June 12, 1883 – September 21, 1957) was an Austrian-born American anthropologist. An expert on Indigenous peoples of the Americas, he was instrumental in the development of modern anthropology and has been described as ...

later said that Sapir's fascination with indigenous languages stemmed from the seminar with Boas in which Boas used examples from Native American languages to disprove all of Sapir's common-sense assumptions about the basic nature of language. Sapir's 1905 Master's thesis was an analysis of Johann Gottfried Herder's ''Treatise on the Origin of Language'', and included examples from Inuit and Native American languages, not at all familiar to a Germanicist. The thesis criticized Herder for retaining a Biblical chronology, too shallow to allow for the observable diversification of languages, but he also argued with Herder that all of the world's languages have equal aesthetic potentials and grammatical complexity. He ended the paper by calling for a "very extended study of all the various existing stocks of languages, in order to determine the most fundamental properties of language" – almost a program statement for the modern study of linguistic typology, and a very Boasian approach.

In 1906 he finished his coursework, having focused the last year on courses in anthropology and taking seminars such as Primitive Culture with Farrand, Ethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

with Boas, Archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

and courses in Chinese language and culture with Berthold Laufer

Berthold Laufer (October 11, 1874 – September 13, 1934) was a German anthropologist and historical geographer with an expertise in East Asian languages. The American Museum of Natural History calls him, "one of the most distinguished sinologi ...

. He also maintained his Indo-European studies with courses in Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

, Old Saxon, Swedish, and Sanskrit. Having finished his coursework, Sapir moved on to his doctoral fieldwork, spending several years in short term appointments while working on his dissertation.

Early fieldwork

Sapir's first fieldwork was on the Wishram Chinook language in the summer of 1905, funded by the Bureau of American Ethnology. This first experience with Native American languages in the field was closely overseen by Boas, who was particularly interested in having Sapir gather ethnological information for the Bureau. Sapir gathered a volume of Wishram texts, published 1909, and he managed to achieve a much more sophisticated understanding of the Chinook sound system than Boas. In the summer of 1906 he worked on

Sapir's first fieldwork was on the Wishram Chinook language in the summer of 1905, funded by the Bureau of American Ethnology. This first experience with Native American languages in the field was closely overseen by Boas, who was particularly interested in having Sapir gather ethnological information for the Bureau. Sapir gathered a volume of Wishram texts, published 1909, and he managed to achieve a much more sophisticated understanding of the Chinook sound system than Boas. In the summer of 1906 he worked on Takelma

The Takelma (also Dagelma) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Rogue Valley of interior southwestern Oregon.

Most of their villages were sited along the Rogue River. The name ''Takelma'' means "(Those) Along the River".

His ...

and Chasta Costa. Sapir's work on Takelma became his doctoral dissertation, which he defended in 1908. The dissertation foreshadowed several important trends in Sapir's work, particularly the careful attention to the intuition of native speakers regarding sound patterns that later would become the basis for Sapir's formulation of the phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

.

In 1907–1908 Sapir was offered a position at the University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant uni ...

, where Boas' first student Alfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber (June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the first ...

was the head of a project under the California state survey to document the Indigenous languages of California. Kroeber suggested that Sapir study the nearly extinct Yana language

The Yana language (also Yanan) was formerly spoken by the Yana people, who lived in north-central California between the Feather River, Feather and Pit River, Pit rivers in what is now the Shasta County, California, Shasta and Tehama County, Teham ...

, and Sapir set to work. Sapir worked first with Betty Brown, one of the language's few remaining speakers. Later he began work with Sam Batwi, who spoke another dialect of Yana, but whose knowledge of Yana mythology was an important fount of knowledge. Sapir described the way in which the Yana language distinguishes grammatically and lexically between the speech of men and women.

The collaboration between Kroeber and Sapir was made difficult by the fact that Sapir largely followed his own interest in detailed linguistic description, ignoring the administrative pressures to which Kroeber was subject, among them the need for a speedy completion and a focus on the broader classification issues. In the end Sapir didn't finish the work during the allotted year, and Kroeber was unable to offer him a longer appointment.

Disappointed at not being able to stay at Berkeley, Sapir devoted his best efforts to other work, and did not get around to preparing any of the Yana material for publication until 1910, to Kroeber's deep disappointment.

Sapir ended up leaving California early to take up a fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

, where he taught Ethnology and American Linguistics. At Pennsylvania he worked closely with another student of Boas, Frank Speck

Frank Gouldsmith Speck (November 8, 1881 – February 6, 1950) was an American anthropologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania, specializing in the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples among the Eastern Woodland Native Americans of ...

, and the two undertook work on Catawba Catawba may refer to:

*Catawba people, a Native American tribe in the Carolinas

*Catawba language, a language in the Catawban languages family

*Catawban languages

Botany

*Catalpa, a genus of trees, based on the name used by the Catawba and other N ...

in the summer of 1909. Also in the summer of 1909, Sapir went to Utah with his student J. Alden Mason. Intending originally to work on Hopi, he studied the Southern Paiute language

Colorado River Numic (also called Ute , Southern Paiute , Ute–Southern Paiute, or Ute-Chemehuevi ), of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family, is a dialect chain that stretches from southeastern California to Colorado. Individual ...

; he decided to work with Tony Tillohash, who proved to be the perfect informant. Tillohash's strong intuition about the sound patterns of his language led Sapir to propose that the phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

is not just an abstraction existing at the structural level of language, but in fact has psychological reality for speakers.

Tillohash became a good friend of Sapir, and visited him at his home in New York and Philadelphia. Sapir worked with his father to transcribe a number of Southern Paiute songs that Tillohash knew. This fruitful collaboration laid the ground work for the classical description of the Southern Paiute language published in 1930, and enabled Sapir to produce conclusive evidence linking the Shoshonean languages to the Nahuan languages

The Nahuan or Aztecan languages are those languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family that have undergone a sound change, known as Whorf's law, that changed an original *t to before *a. Subsequently, some Nahuan languages have changed this to ...

– establishing the Uto-Aztecan language family

Uto-Aztecan, Uto-Aztekan or (rarely in English) Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The na ...

. Sapir's description of Southern Paiute is known by linguistics as "a model of analytical excellence".

At Pennsylvania, Sapir was urged to work at a quicker pace than he felt comfortable. His "Grammar of Southern Paiute" was supposed to be published in Boas' '' Handbook of American Indian Languages'', and Boas urged him to complete a preliminary version while funding for the publication remained available, but Sapir did not want to compromise on quality, and in the end the ''Handbook'' had to go to press without Sapir's piece. Boas kept working to secure a stable appointment for his student, and by his recommendation Sapir ended up being hired by the Canadian Geological Survey, who wanted him to lead the institutionalization of anthropology in Canada. Sapir, who by then had given up the hope of working at one of the few American research universities, accepted the appointment and moved to Ottawa.

In Ottawa

In the years 1910–25 Sapir established and directed the Anthropological Division in theGeological Survey of Canada

The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC; french: Commission géologique du Canada (CGC)) is a Canadian federal government agency responsible for performing geological surveys of the country, developing Canada's natural resources and protecting the e ...

in Ottawa. When he was hired, he was one of the first full-time anthropologists in Canada. He brought his parents with him to Ottawa, and also quickly established his own family, marrying Florence Delson, who also had Lithuanian Jewish roots. Neither the Sapirs nor the Delsons were in favor of the match. The Delsons, who hailed from the prestigious Jewish center of Vilna

Vilnius ( , ; see also #Etymology and other names, other names) is the capital and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the munic ...

, considered the Sapirs to be rural upstarts and were less than impressed with Sapir's career in an unpronounceable academic field. Edward and Florence had three children together: Herbert Michael, Helen Ruth, and Philip.

Canada's Geological Survey

As director of the Anthropological division of the Geological Survey of Canada, Sapir embarked on a project to document the Indigenous cultures and languages of Canada. His first fieldwork took him toVancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest by ...

to work on the Nootka language. Apart from Sapir the division had two other staff members, Marius Barbeau

Charles Marius Barbeau, (March 5, 1883 – February 27, 1969), also known as C. Marius Barbeau, or more commonly simply Marius Barbeau, was a Canadian ethnographer and folklorist who is today considered a founder of Canadian anthropology. A ...

and Harlan I. Smith. Sapir insisted that the discipline of linguistics was of integral importance for ethnographic description, arguing that just as nobody would dream of discussing the history of the Catholic Church without knowing Latin or study German folksongs without knowing German, so it made little sense to approach the study of Indigenous folklore without knowledge of the indigenous languages. At this point the only Canadian first nation

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

languages that were well known were Kwakiutl, described by Boas, Tshimshian and Haida. Sapir explicitly used the standard of documentation of European languages, to argue that the amassing knowledge of indigenous languages was of paramount importance. By introducing the high standards of Boasian anthropology, Sapir incited antagonism from those amateur ethnologists who felt that they had contributed important work. Unsatisfied with efforts by amateur and governmental anthropologists, Sapir worked to introduce an academic program of anthropology at one of the major universities, in order to professionalize the discipline.

Sapir enlisted the assistance of fellow Boasians: Frank Speck

Frank Gouldsmith Speck (November 8, 1881 – February 6, 1950) was an American anthropologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania, specializing in the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples among the Eastern Woodland Native Americans of ...

, Paul Radin

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

and Alexander Goldenweiser, who with Barbeau worked on the peoples of the Eastern Woodlands: the Ojibwa, the Iroquois, the Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

and the Wyandot

Wyandot may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Wyandot people, also known as the Huron

* Wyandot language

Wyandot (sometimes spelled Wandat) is the Iroquoian language traditionally spoken by the people known variously as Wyandot or Wya ...

. Sapir initiated work on the Athabascan languages

Athabaskan (also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large family of indigenous languages of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, Pacific C ...

of the Mackenzie valley and the Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

, but it proved too difficult to find adequate assistance, and he concentrated mainly on Nootka and the languages of the North West Coast.

During his time in Canada, together with Speck, Sapir also acted as an advocate for Indigenous rights, arguing publicly for introduction of better medical care for Indigenous communities, and assisting the Six Nation Iroquois in trying to recover eleven wampum

Wampum is a traditional shell bead of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of Native Americans. It includes white shell beads hand-fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell and white and purple beads made from the quahog or Western Nor ...

belts that had been stolen from the reservation and were on display in the museum of the University of Pennsylvania. (The belts were finally returned to the Iroquois in 1988.) He also argued for the reversal of a Canadian law prohibiting the Potlatch ceremony of the West Coast tribes.

Work with Ishi

In 1915 Sapir returned to California, where his expertise on the Yana language made him urgently needed. Kroeber had come into contact with Ishi, the last native speaker of the Yahi language, closely related to Yana, and needed someone to document the language urgently. Ishi, who had grown up without contact to whites, was monolingual in Yahi and was the last surviving member of his people. He had been adopted by the Kroebers, but had fallen ill with

In 1915 Sapir returned to California, where his expertise on the Yana language made him urgently needed. Kroeber had come into contact with Ishi, the last native speaker of the Yahi language, closely related to Yana, and needed someone to document the language urgently. Ishi, who had grown up without contact to whites, was monolingual in Yahi and was the last surviving member of his people. He had been adopted by the Kroebers, but had fallen ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

, and was not expected to live long. Sam Batwi, the speaker of Yana who had worked with Sapir, was unable to understand the Yahi variety, and Krober was convinced that only Sapir would be able to communicate with Ishi. Sapir traveled to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

and worked with Ishi over the summer of 1915, having to invent new methods for working with a monolingual speaker. The information from Ishi was invaluable for understanding the relation between the different dialects of Yana. Ishi died of his illness in early 1916, and Kroeber partly blamed the exacting nature of working with Sapir for his failure to recover. Sapir described the work: "I think I may safely say that my work with Ishi is by far the most time-consuming and nerve-racking that I have ever undertaken. Ishi's imperturbable good humor alone made the work possible, though it also at times added to my exasperation".

Moving on

The

The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

took its toll on the Canadian Geological Survey, cutting funding for anthropology and making the academic climate less agreeable. Sapir continued work on Athabascan, working with two speakers of the Alaskan languages Kutchin and Ingalik. Sapir was now more preoccupied with testing hypotheses about historical relationships between the Na-Dene languages

Na-Dene (; also Nadene, Na-Dené, Athabaskan–Eyak–Tlingit, Tlina–Dene) is a family of Native American languages that includes at least the Athabaskan languages, Eyak, and Tlingit languages. Haida was formerly included, but is now consider ...

than with documenting endangered languages, in effect becoming a theoretician. He was also growing to feel isolated from his American colleagues. From 1912 Florence's health deteriorated due to a lung abscess

Lung abscess is a type of liquefactive necrosis of the lung tissue and formation of cavities (more than 2 cm) containing necrotic debris or fluid caused by microbial infection.

This pus-filled cavity is often caused by aspiration, which ma ...

, and a resulting depression. The Sapir household was largely run by Eva Sapir, who did not get along well with Florence, and this added to the strain on both Florence and Edward. Sapir's parents had by now divorced and his father seemed to suffer from a psychosis, which made it necessary for him to leave Canada for Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, where Edward continued to support him financially. Florence was hospitalized for long periods both for her depressions and for the lung abscess, and she died in 1924 due to an infection following surgery, providing the final incentive for Sapir to leave Canada. When the University of Chicago offered him a position, he happily accepted.

During his period in Canada, Sapir came into his own as the leading figure in linguistics in North America. Among his substantial publications from this period were his book on ''Time Perspective in the Aboriginal American Culture'' (1916), in which he laid out an approach to using historical linguistics to study the prehistory of Native American cultures. Particularly important for establishing him in the field was his seminal book '' Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech'' (1921), which was a layman's introduction to the discipline of linguistics as Sapir envisioned it. He also participated in the formulation of a report to the American Anthropological Association regarding the standardization of orthographic principles for writing Indigenous languages.

While in Ottawa, he also collected and published French Canadian Folk Songs, and wrote a volume of his own poetry. His interest in poetry led him to form a close friendship with another Boasian anthropologist and poet, Ruth Benedict

Ruth Fulton Benedict (June 5, 1887 – September 17, 1948) was an American anthropologist and folklorist.

She was born in New York City, attended Vassar College, and graduated in 1909. After studying anthropology at the New School of Social Re ...

. Sapir initially wrote to Benedict to commend her for her dissertation on "The Guardian Spirit", but soon realized that Benedict had published poetry pseudonymously. In their correspondence the two critiqued each other's work, both submitting to the same publishers, and both being rejected. They also were both interested in psychology and the relation between individual personalities and cultural patterns, and in their correspondences they frequently psychoanalyzed each other. However, Sapir often showed little understanding for Benedict's private thoughts and feelings, and particularly his conservative gender ideology jarred with Benedict's struggles as a female professional academic. Though they were very close friends for a while, it was ultimately the differences in worldview and personality that led their friendship to fray.

Before departing Canada, Sapir had a short affair with Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901 – November 15, 1978) was an American cultural anthropologist who featured frequently as an author and speaker in the mass media during the 1960s and the 1970s.

She earned her bachelor's degree at Barnard C ...

, Benedict's protégé at Columbia. But Sapir's conservative ideas about marriage and the woman's role were anathema to Mead, as they had been to Benedict, and as Mead left to do field work in Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, the two separated permanently. Mead received news of Sapir's remarriage while still in Samoa, and burned their correspondence there on the beach.

Chicago years

Settling in Chicago reinvigorated Sapir intellectually and personally. He socialized with intellectuals, gave lectures, participated in poetry and music clubs. His first graduate student at Chicago wasLi Fang-Kuei

Li Fang-Kuei ( Chinese: 李方桂, Cantonese: Lei5 Fong1 Gwai3 ej˩˨ fɔŋ˦ gʷaj˧, Mandarin: Lǐ Fāngguì i˨ faŋ˦ gʷej˥˩ 20 August 190221 August 1987) was a Chinese linguist known for his studies of the varieties of Chinese, his r ...

. The Sapir household continued to be managed largely by Grandmother Eva, until Sapir remarried in 1926. Sapir's second wife, Jean Victoria McClenaghan, was sixteen years younger than he. She had first met Sapir when a student in Ottawa, but had since also come to work at the University of Chicago's department of Juvenile Research. Their son Paul Edward Sapir was born in 1928. Their other son J. David Sapir

J. David Sapir, son of Edward Sapir, is a linguist, anthropologist and photographer. He is Emeritus professor of Anthropology at the University of Virginia. He is known for his research on Jola languages

Jola (Joola) or Diola is a dialect cont ...

became a linguist and anthropologist specializing in West African Languages, especially Jola languages

Jola (Joola) or Diola is a dialect continuum spoken in Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau. It belongs to the Bak branch of the Niger–Congo language family.

Name

The name ''Jola'' is an exonym, and may be from the Mandinka word ''joolaa ...

. Sapir also exerted influence through his membership in the Chicago School of Sociology, and his friendship with psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan

Herbert "Harry" Stack Sullivan (February 21, 1892, Norwich, New York – January 14, 1949, Paris, France) was an American Neo-Freudian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who held that "personality can never be isolated from the complex interpersonal r ...

.

At Yale

From 1931 until his death in 1939, Sapir taught atYale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, where he became the head of the Department of Anthropology. He was invited to Yale to found an interdisciplinary program combining anthropology, linguistics and psychology, aimed at studying "the impact of culture on personality". While Sapir was explicitly given the task of founding a distinct anthropology department, this was not well received by the department of sociology who worked by William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and classical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University—where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology—and be ...

's "Evolutionary sociology", which was anathema to Sapir's Boasian approach, nor by the two anthropologists of the Institute for Human Relations Clark Wissler

Clark David Wissler (September 18, 1870 – August 25, 1947) was an American anthropologist, ethnologist, and archaeologist.

Early life

Clark David Wissler was born in Cambridge City, Indiana on September 18, 1870 to Sylvania (née Needler) an ...

and G. P. Murdock.Darnell 1998 Sapir never thrived at Yale, where as one of only four Jewish faculty members out of 569 he was denied membership to the faculty club where the senior faculty discussed academic business.

At Yale, Sapir's graduate students included Morris Swadesh, Benjamin Lee Whorf

Benjamin Lee Whorf (; April 24, 1897 – July 26, 1941) was an American linguist and fire prevention engineer. He is known for " Sapir–Whorf hypothesis," the idea that differences between the structures of different languages shape how the ...

, Mary Haas

Mary Rosamond Haas (January 23, 1910 – May 17, 1996) was an American linguist who specialized in North American Indian languages, Thai, and historical linguistics. She served as president of the Linguistic Society of America. She was elected ...

, Charles Hockett

Charles Francis Hockett (January 17, 1916 – November 3, 2000) was an American linguist who developed many influential ideas in American structuralist linguistics. He represents the post- Bloomfieldian phase of structuralism often referred to as ...

, and Harry Hoijer

Harry Hoijer (September 6, 1904 – March 11, 1976) was a linguist and anthropologist who worked on primarily Athabaskan languages and culture. He additionally documented the Tonkawa language, which is now extinct. Hoijer's few works make up the ...

, several of whom he brought with him from Chicago. Sapir came to regard a young Semiticist

Semitic studies, or Semitology, is the academic field dedicated to the studies of Semitic languages and literatures and the history of the Semitic-speaking peoples. A person may be called a ''Semiticist'' or a ''Semitist'', both terms being equi ...

named Zellig Harris

Zellig Sabbettai Harris (; October 23, 1909 – May 22, 1992) was an influential American linguist, mathematical syntactician, and methodologist of science. Originally a Semiticist, he is best known for his work in structural linguistics and dis ...

as his intellectual heir, although Harris was never a formal student of Sapir. (For a time he dated Sapir's daughter.)Reported by Regna Darnell

Regna Darnell (born July 10, 1943, Cleveland, Ohio) is an American-Canadian anthropologist and professor of Anthropology and First Nations Studies at the University of Western Ontario, where she has founded the First Nations Studies Program.

Ov ...

, Sapir's biographer (p.c. to Bruce Nevin). In 1936 Sapir clashed with the Institute for Human Relations over the research proposal by anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker

Hortense Powdermaker (December 24, 1900 – June 16, 1970) was an American anthropologist best known for her ethnographic studies of African Americans in rural America and of Hollywood.

Early life and education

Born to a Jewish family, Powdermak ...

, who proposed a study of the black community of Indianola, Mississippi. Sapir argued that her research should be funded instead of the more sociological work of John Dollard

John Dollard (29 August 1900 – 8 October 1980) was an American psychologist and social scientist known for his studies on race relations in America and the frustration-aggression hypothesis he proposed with Neal E. Miller and others.

Life and ...

. Sapir eventually lost the discussion and Powdermaker had to leave Yale.

In the summer of 1937 while teaching at the Linguistic Institute of the Linguistic Society of America

The Linguistic Society of America (LSA) is a learned society for the field of linguistics. Founded in New York City in 1924, the LSA works to promote the scientific study of language. The society publishes three scholarly journals: ''Language'', ...

in Ann Arbor, Sapir began having problems with a heart condition that had initially been diagnosed a couple of years earlier. In 1938, he had to take a leave from Yale, during which Benjamin Lee Whorf taught his courses and G. P. Murdock advised some of his students. After Sapir's death in 1939, G. P. Murdock became the chair of the anthropology department. Murdock, who despised the Boasian paradigm of cultural anthropology, dismantled most of Sapir's efforts to integrate anthropology, psychology, and linguistics.

Anthropological thought

Sapir's anthropological thought has been described as isolated within the field of anthropology in his own days. Instead of searching for the ways in which culture influences human behavior, Sapir was interested in understanding how cultural patterns themselves were shaped by the composition of individual personalities that make up a society. This made Sapir cultivate an interest in individual psychology and his view of culture was more psychological than many of his contemporaries. It has been suggested that there is a close relation between Sapir's literary interests and his anthropological thought. His literary theory saw individual aesthetic sensibilities and creativity to interact with learned cultural traditions to produce unique and new poetic forms, echoing the way that he also saw individuals and cultural patterns to dialectically influence each other.Breadth of languages studied

Sapir's special focus among American languages was in the Athabaskan languages, a family which especially fascinated him. In a private letter, he wrote: "Dene

The Dene people () are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. ''Dene'' is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" ha ...

is probably the son-of-a-bitchiest language in America to actually ''know''...most fascinating of all languages ever invented." Sapir also studied the languages and cultures of Wishram Chinook, Navajo, Nootka, Colorado River Numic, Takelma

The Takelma (also Dagelma) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Rogue Valley of interior southwestern Oregon.

Most of their villages were sited along the Rogue River. The name ''Takelma'' means "(Those) Along the River".

His ...

, and Yana

Yana may refer to:

Locations

*Yana, Burma, a village in Hkamti Township in Hkamti District in the Sagaing Region of northwestern Burma

*Yana, India, a village in the Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka, India

* Yana, Nigeria, an administrative ca ...

. His research on Southern Paiute, in collaboration with consultant Tony Tillohash, led to a 1933 article which would become influential in the characterization of the phoneme

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

.

Although noted for his work on American linguistics, Sapir wrote prolifically in linguistics in general. His book ''Language'' provides everything from a grammar-typological classification of languages (with examples ranging from Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

to Nootka) to speculation on the phenomenon of language drift, and the arbitrariness of associations between language, race, and culture. Sapir was also a pioneer in Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

studies (his first language) in the United States (cf. ''Notes on Judeo-German phonology'', 1915).

Sapir was active in the international auxiliary language movement. In his paper "The Function of an International Auxiliary Language", he argued for the benefits of a regular grammar and advocated a critical focus on the fundamentals of language, unbiased by the idiosyncrasies of national languages, in the choice of an international auxiliary language.

He was the first Research Director of the International Auxiliary Language Association

The International Auxiliary Language Association, Inc. (IALA) was an American organisation founded in 1924 to "promote widespread study, discussion and publicity of all questions involved in the establishment of an auxiliary language, together wi ...

(IALA), which presented the Interlingua

Interlingua (; ISO 639 language codes ia, ina) is an international auxiliary language (IAL) developed between 1937 and 1951 by the American International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA). It ranks among the most widely used IALs and is t ...

conference in 1951. He directed the Association from 1930 to 1931, and was a member of its Consultative Counsel for Linguistic Research from 1927 to 1938. Sapir consulted with Alice Vanderbilt Morris

Alice Vanderbilt Shepard Morris (December 7, 1874 – August 15, 1950) was a member of the Vanderbilt family. She co-founded the International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA).

Early life

Alice was born on December 7, 1874 in New York. S ...

to develop the research program of IALA.Falk, Julia S. "Words without grammar: linguists and the international language movement in the United States", ''Language and Communication'', 15(3): pp. 241–259. Pergamon, 1995.

Selected publications

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * *Essays and articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Biographies

* * * * *Correspondence

*References

External links

National Academy of Sciences biography

at spartan.ac.brocku.ca

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sapir, Edward 1884 births 1939 deaths People from Lębork Lithuanian Jews People from the Province of Pomerania American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent German emigrants to the United States Jewish American social scientists Linguists from the United States Linguists of Yiddish Anthropological linguists Interlingua Columbia College (New York) alumni University of Chicago faculty Yale University faculty Columbia University faculty Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Yale Sterling Professors Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni Linguists of Na-Dene languages Linguists of Navajo Linguists of Algic languages Linguists of Siouan languages Linguists of Salishan languages Linguists of Hokan languages Linguists of Uto-Aztecan languages Linguists of Chinookan languages Linguists of Wakashan languages Linguists of Penutian languages Paleolinguists DeWitt Clinton High School alumni Linguistic Society of America presidents Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People from the Lower East Side 20th-century linguists Jewish anthropologists Linguists of indigenous languages of the Americas 20th-century American anthropologists Presidents of the American Folklore Society